| After tacking the

interlinings on I began the buttonholes from the bottom

upwards. When I got to the opened ones I first sewed a row

on machine stitch around them, then cut them open and

reinforced the edges with zigzag. My poor old much used

zigzag machine didn't manage to get the stitches tight

enough, so I made them while visiting my parents on my

Mom's machine (The first sewing machine I have used in my

life, by the way). |

|

|

So far

so good, but when I began to cover these reinforcing

stitches on the buttonhole thread I realized that I had

made the decorative ones at the bottom edge more narrow.

I did not want to remake my reinforcing stitching

narrower as I was afraid that the loosely woven

interlining might break if stitched too near the edge.

So I made them as I had planned, then took a critical

eye and finally decided that the contrast to the

narrower buttonholes was too visible, therefore the

latter had to go. I carefully picked out the thread and

remade them roughly as thick as the opened ones.

|

|

|

I had already taken a liking to the

more slender buttonholes and at first the new ones

looked too heavy, but as I did not dare to make the

opened buttonholes slimmer there was no other way. At

this stage the pocket flaps were already finished, with

buttonholes of the slimmer variety, but as they did not

sit directly next to front buttonholes I left them

alone. Well, happily I encountered the problem already

with the waistcoat before beginning the coat.

Next I

made the triangular pocket opening, reinforced the edges

with hand stitching and then sewed on the other layer of

the pocket bag, and for the last thing attached the

pocket flap. I had very stupidly cut the pocket

interlining to stop just just before the buttons, so I

sewed pieces of linen band on the underside to support

the large buttons.

|

|

|

Which

brings us to the matter of the buttons. The larger

buttons for the coat and waistcoat were much nicer to

make than the smaller ones. Along with the pocket edge

of the breeches the buttons were the only parts of the

project where I made use of unforgivably modern iron-on

interfacing. I was too afraid the tiny seam allowances

on the tightly gathered button tops would fray without.

I also added a piece of thick but soft wool for padding

between the button and the top layer, which made them

nicely rounded. Tracing the pieces, cutting them and

ironing the interfacings took some time for the total 68

buttons. Then I could always keep some pieces and

buttons in my sewing purse until they were all covered.

|

|

I tried to improve my technique from the breeches buttons

by gathering the edge regularly (it was made easy by the

pattern) and then joining the ridges that had formed. On

the larger button the allowances had more space, but the

underside still became quite thick.

To

continue about the waistcoat, after finishing the

pockets it was time to put a lining on the fronts. The

whole matter of lining this suit had caused me some

headaches, mainly concerning what to use for it. The

decision was simple for the breeches but the coat was

the main problem. In the Costume Close Up suit, and most

of other sources I've studied the coat is described

lined in silk except the top part of the back (and

possibly sleeves too) with linen, as the latter won't

show when the coat is worn. My problem was what to use

for the “silk” part.

|

|

|

My

textile knowledge of the period is not very strong when

it comes to what the textiles of the period actually

were like (apart from fiber content), the feel, the

weight etc, having seen most of the originals only from

photographs or from some distance behind a glass. As my

fashion fabric, the upholstery viscose was not that

stiff I thought it could use some backing from the

lining added to the interlinings. My budget did not

allow a silk taffeta lining, which would of course be

insane with a cheaper fashion fabric too, and polyester

taffeta would be too stiff, not very nice to work with

and would not breathe at all. Modern ultra thin lining

satin is too flimsy, and the bit heavier viscose one

used for coats etc can be annoying to work with too. I

had in my mind some sort of combination of the flimsy

lining backed with linen, but then I happened to find a

length of heavier satin (probably viscose) at my

favorite second hand shop. It was in a perfect cream

shade. I decided to use it, possibly backed with linen

at some parts on the coat. I could, however, decide on

the coat later.

The

Costume Close Up waistcoat (No 17, Suit coat, waistcoat

and breeches, dated 1765-1790) is lined mostly with

linen but has silk facings at the front edges and

skirts. This seemed to me a very neat way of doing

things, as especially the top corners easily turn up

with the shirt ruffles and a satin lining would look

nice there. I did, however decide to leave out the skirt

facings with this longer waistcoat.

|

|

|

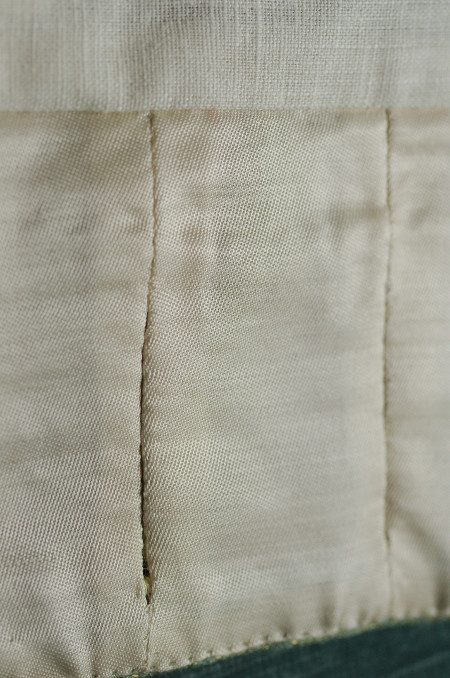

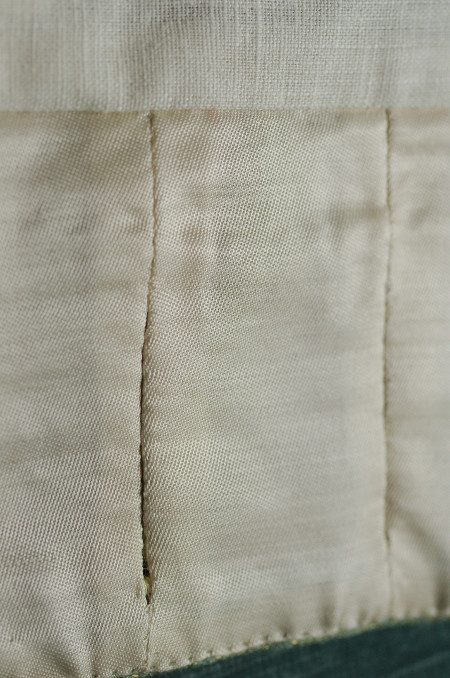

The

picture of the open waistcoat shows most frustratingly

only the button side of the lining, so there is no clue

how the buttonhole part was actually finished. I have

read before vague descriptions of “cutting the lining

open at the buttonholes and sewing it on their edges”,

which sounds to me courting fraying. I've seen it work

well in woollen military garments, but there is no way

I'm going to try that for viscose satin. Happily the

brilliant “At the

Sign of The Golden Scissors”-blog happened to post

about riding habits with

a clear photograph of the “pieced facing”-technique,

where the lining is cut on separate pieces joined at the

ends of the buttonholes. So, that was what I would do.

In a

perfect world where all measurements are exact and all

pieces magically match I might have been able to join

the pieces by machine and just leave the seam open at

the right part, but in this reality I thought that no

matter how carefully I'd cut them all the pieces would

not settle perfectly between their buttonholes without

some adjusting and re-sewing, so I sewed them on the

interlining and the buttonhole stitch by hand one by

one. This of course took some time, but the meticulously

neat result was well worth the effort.

|

|

|

I pinned

the rest of the facing and attached it on the front

edges with hand stitching through all layers. I used a

row of stab stitches, here and elsewhere in the suit, as

the proper “Le

point a rabattre sous la main”-stitch is hard to

make through the heavy interlining. After the facing

came the rest of the linen lining. On the shoulder I

pinned it just a bit smaller than the fashion fabric

to follow the curve of the shoulder. On the shoulder

and side seams I just machine stitched the seam

allowances together.

|

|

|

The fronts and back

being now both finished it only remained to join

them. On the silk waistcoat I had sewed the back

piece between the two layers of fronts at shoulder

and side seam, which had resulted in a giant bulky

seam allowance at the shoulder seam ends as the

front pieces curve out. Now I tried to join them the

other way around. I had left the side seams and the

shoulder-neckline-part open at the back, and now

sewed the front piece on the top layer of the back.

Then I pressed the seam allowances to turn towards

the back piece and the back neck allowances to turn

under. Then I pinned the bottom layer of the back

with the seam allowances turned under, just covering

the machine stitch, and at the neck to turn a few

millimetres from the edge.

|

|

| I finished the neck by

hand and added a cotton band to prevent it from

stretching. I have no idea if the latter was used in

the period, but it seemed like a goof idea to me. For

the last thing I top-stitched all the seams to fix the lining. The

result looks neat also from the inside. |

|

|

The waistcoat was thus

finished. As said, I had trusted my well-prover

pattern and had not had a single fitting while

making it. Now it turned out that I had obviously

picked an older version of the back piece pattern

without the back lacing, as the edges came together

with no gap in between. Well, of course it looks

nice and neat without a gap, but it kind of makes

the lacing useless as means of adjusting the size

smaller. Jarno assured me, though, that at this

stage of life he is not likely to lose weight.

Anyway, despite this the waistcoat looks quite was

it should be.

The

Saga of the Green Suit is continued in page 4

>>

|

|